Go

Table of Contents

Go is a programming language that focuses on simplicity and speed. It’s simpler than other languages, so it’s quicker to learn. And it lets you harness the power of today’s multicore computer processor, so your programs run faster.

History of Go⌗

Back in 2007, the search engine Google had a problem. They had to maintain programs with millions of line of code. Before they could test new changes, they had to compile the code into runnable form, a process which at the time took the better part of an hour. Needless to say, this was bad for developer productivity.

So Google engineers Robert Griesemer, Rob Pike, and Ken Thompson sketched out some goals for a new language:

- Fast Compilation

- Less cumbersome code

- Unused memory freed automatically (garbage collection)

- Easy-to-write software that does serval operations simultaneously (concurrency)

- Good support for processor with multiple cores

After a couple years of work, Google had created Go: a language that was fast to write code for and produced programs that were fast to compile and run. The project switched to an open source license in 2009. It’s now free for anyone to use.

If you’re writing a command-line tool, Go can produce executable files for Windows, MacOS, and Linux, all from the same source code. If you’re writing a web server, it can help you handle many users connecting at once. And no matter what you’re what you’re writing, it will help you ensure that your code is easier to maintain.

Syntax Basics⌗

Go Playground⌗

The easiest way to try Go is to visit Go Playground in your web browser. It is simple editor where you can enter Go code and run it on their servers. The result is displayed right there in your browser.

Note: Go Playground requires stable internet connection. If you don’t, see Install Go on your system.

Let’s try out play ground:

- Open Go Playground in your browser.

- There will be hello world program already written.

- Click the Format button, which will automatically reformat your code according to Go conventions.

- Click the Run button.

You should see “Hello, World!” displayed at the bottom of the screen.

Congratulations, you’ve just run your first Go program🥳!

Go file layout⌗

Now let’s look at the code and figure out what it actually means…

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello, World")

}

Every Go file has three sections:

- The

packageclause - Any

importstatements - The actual code

Package: A package is a collection of code that all does similar things, like formatting strings or drawing images. The package clause gives the name of the package that this file’s code will become a part of. In this case, we use the special packagemain, which is required if this code is going to be run directly (usually from the terminal).import: Go files almost always have one or moreimportstatements. Each file needs toimportother packages before its code can use the code those other packages contain. Loading all the Go code on your computer at once would result in a big, slow program, so instead you specify only the package you need by importing them.actual code: The last part of every Go file is the actual code, which is often split up into one or more functions. Afunctionis a group of code that youcall (run)from other places in your program. When a Go program is run, it looks for a function namedmainand runs that first, which is why we need this functionmain.

Below is the code with what it does in comments:

// This line says the rest of the code in

// this file belongs to the "main" package

package main

// This says we will be using text-formatting

// code from the "fmt" package

import "fmt"

// The "main" function is special; it gets run

// first when your program runs.

func main() {

// This line displays ("print") "Hello, World" in

// your terminal (or web browser, if you're using the Go Playground)

//

// It does this by calling the "Println" function

// from the "fmt" package

fmt.Println("Hello, World")

}

Function: A function is a group of one or more lines of code that you can call (run) from other places in your program.

Note: When a Go program is run, it looks for a function named

mainand runs that first.

No Semicolons⌗

As you can see in our program there are no semicolons to separate statements in Go, we can use semicolons but it’s not required (in fact, it’s generally frowned upon).

Like C, Go’s formal grammar uses semicolons to terminate statements, but unlike in C, those semicolons do not appear in the source. Instead the lexer uses a simple rule to insert semicolons automatically as it scans, so the input text is mostly free of them.

If you want to know more how it works you check Go’s official doc https://go.dev/doc/effective_go#semicolons

Formatting⌗

Formatting issues are the most contentious but the least important. People may prefer different formatting styles, thus when another developer or person reads the same code it may take some time for him to grasp if he is not accustomed to the same formatting style. It will be easier if everyone formats their documents in the same way.

With Go we take an unusual approach and let the machine take care of most formatting issues. The Go compiler comes with a standard formatting tool, called go fmt. The go fmt program reads a Go program and emits the source in a standard style of indentation and vertical alignment, retaining and if necessary reformatting comments.

Next time whenever you share your code, other Go developers will expect it to be in the standard Go format. With Go all you have to do is run go fmt.

If you want to try its simple version, head over to the Go playground, write some buggy or unformatted code, and hit the format button.

Comments⌗

Go provides C style /* */ block comments and C++ style // line comments. Most block comments appear as package comments but are useful within an expression or to disable large blocks of code; Otherwise usually line comments are used.

Comments that appear before a top-level declaration, with no intervening newlines, are considered to document the declaration itself. For example: In the above Hello World programme with comments, all comments will be used in Go Documents. These doc comments are the primary documentation for given Go package or command.

For more about doc comments, see Go Doc Comments.

Names⌗

Names are as important in Go as in any other language. Go has one simple set of rules that apply to the names of variables, functions, and types:

A name must begin with letter, and can have any number of additional letters and numbers.

The visibility of a name outside a package is determined by below points:

- If the name of a variable, function, or type begins with a Capital letter, it is considered Exported and can be accessed from packages outside the current one.

Example- As you have seen in above hello world program. ThePinfmt.Printlnis capitalized: so it can be used from the main package or any other. - If the name begins with a Lowercase letter, it is considered Unexported and only be accessed within the current package.

- If the name of a variable, function, or type begins with a Capital letter, it is considered Exported and can be accessed from packages outside the current one.

Above the only rules enforced by the language. But the Go community follows some additional conventions as well:

If a name consists of multiple words, each word after the first should be capitalized, and they should be attached together without spaces between them, like this: topRank, RetryConnection… This style is often called Camel Case because the capitalized letter look like the humps of a camel.

When the meaning of a name is obvious from the context, the Go community’s convention is to abbreviate it: to use

iinstead ofindex,maxinstead ofmaximum…

MixedCaps⌗

The convention in Go is to use MixedCaps or mixedCaps rather than underscores to write multiword names.

Package Names⌗

Good package names make code better. A package’s names provides context for its contents, making it easier for developer/user to understand what the package is for and how to use it. The name also helps package maintainers determine what does and does not belong in the package as it evolves. Well-named packages make it easier to find the code you need.

Guideline⌗

It’s helpful if everyone using the package can the same name to refer to its contents, which implies that the package name should be good: short, concise, evocative. By convention, packages are given lower case, single-word names; there should be no need for under_scores or mixedCaps. They are often simple nouns, such as:

- time (provides functionality for measuring and displaying time)

- list (implements a doubly linked list)

- http (provides HTTP client and server implementations)

Below are example for bad naming styles in Go:

- computeServiceClient

- priority_queue

Abbreviate judiciously. Package names may be abbreviated when the abbreviation is familiar to the programmer. Widely-used packages often have compressed names:

- strconv (string conversion)

- syscall (system call)

- fmt (formatted I/O)

Note:- If abbreviating a package name makes it ambiguous or unclear, don’t do it.

Another convention is that the package name is the base name of its source directory; the package in src/encoding/base64 is imported as "encoding/base64" but has name base64, not encoding_base64 and not encodingBase64.

Another short example is once.Do; once.Do(setup) reads well and would not be improved by writing once.DoOrWaitUntilDone(setup). Long names don’t automatically make things more readable. A helpful doc comment can often be more valuable than an extra long name.

Interface Names⌗

By convention, one-method interfaces are named by the method name plus and -er suffix or similar modification to construct an agent noun; Reader, Writer, Formatter, CloseNotifier etc.

Declaration Variables⌗

In Go, a variable is a piece of storage containing a value. You can give a variable a name by using a variable declaration. Just use the var keyword followed by the desired name and the type of values the variable will hold.

Variable declaration syntax:

var name string

var:- It is a keyword.name:- It will be a variable name that you want to access in your programme.string:- It will be any datatype that the variable will hold data for. (Go-supported datatype)

Once you declare a variable, you can assign any value of that type to it with = sign.

var name string = "Jerry"

You can assign values to multiple variables in the same statement. Just place multiple variable names on the left side of =, and the same number of values on the right side, separated with commas (,).

Syntax for assign multiple variables at once:

var length, width float64 = 1.2, 2.4

You can assign new values to existing variables, but they need to be values of the same type like you can’t assign int variable value to string type variable. Go’s static typing ensures you don’t accidentally assign the wrong kind of value to a variable.

Short Variable Declaration⌗

As we seen in the above section we can declare variables and assign them values on the same line. But if you know what the initial value of a variable is going to be as soon as you declare it, it’s more typical to use a short variable declaration. Instead of explicitly declaring the type of the variable and later assigning to it with =, you do both at once using :=.

Here are our previous examples with short variable declaration :

name := jerryinstead ofvar name string = "Jerry"length, width := 1.2, 2.4instead ofvar length, width float64 = 1.2, 2.4

There’s no need to explicitly declare the variable’s type; the type of the value assigned to the variable becomes the type of that variable.

Because short variable declarations are so convenient and concise, they’re used more often than regular declarations. You’ll still see both forms occasionally, though, so it’s important to be familiar with both.

Pointers⌗

Functions⌗

A function is a group of statements that together perform a task. Function can be used to:

- Reuse code in multiple places.

- Make code more organized and readable.

- Hide implementation details.

- Improve code performance.

Functions are declared using the func keyword, followed by the function name, a list of parameters in parentheses (), and a block of code. The function body is enclosed in curly braces ({ and }). A function can take zero or more arguments.

Syntax for function in Go: func funcName(var1 dataType, var2 dataType,... varN dataType) returnType {}

Creating Function and Calling Function⌗

Let’s create a sample addition program which will contains function with name add() it will take 2 arguments x and y. Which will be int type and return int (Don’t worry we will check return and data types next sections.).

package main

import "fmt"

func add(x, y int) int {

return x + y

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(add(15, 10))

}

In the above Addition Function program we have two functions. The first is main(), which doesn’t take any arguments (arguments are passed inside rounded brackets ()). The second function is our add function, which you can see we have started with the func keyword to declare a function, followed by the function name add(), and we have passed two arguments x and y, which are type of int. When two or more consecutively named function parameters or arguments share a type, you can omit the type from all but the last.

In the above example, we shortened:

x int, y int to x, y int

The function is returning int data type, which is single value, with return statement statement of x + y, which is an addition of numbers.

To call this function, we need to type the function name (add in this case) and a pair of parentheses with arguments separated by a comma (,) in our case, which is 15, 10.

A parameter is a variable, local to a function, whose value is set when the function is called. When the function is run, each parameter will be se to a copy of the value in the corresponding arguments.

If you check the above program Println is also a function. Let’s break down the structure of fmt.Println() and see what is happening here.

fmt.:- It is an package which contain multiple function.Println:-Printlnis function name which resides infmtpackage. To usePrintlnpackage should be imported then only we can access function it offers.():- By using parentheses we are executing the function.

If the function takes a number of arguments and we don’t pass any or provide too few or too many, it will give you an error message saying how many arguments were expected, and you will need to fix your code.

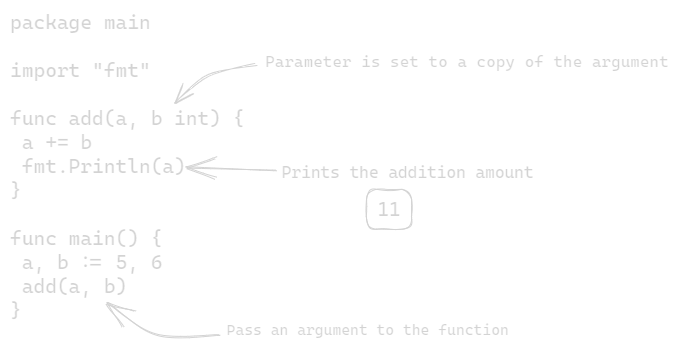

Function parameters receive copies of the arguments⌗

As we mentioned, when you call a function that has parameters declared, you need to provide arguments to the call. The value in each argument is copied to the corresponding parameter variable. It is also called pass-by-value.

Go is a “pass-by-value” language; function parameters receive a copy of the arguments from the function call.

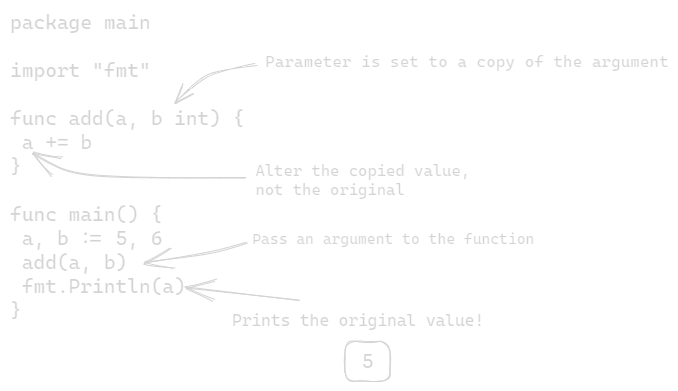

This is fine in most cases. But if you want to pass a variable’s value to a function and have it change the value in some way, you’ll run into trouble. The function can only change the copy of the value in it’s parameter, not the original. So any changes you make within the function won’t be visible outside it!

For example:

Now, we wanted to move the statement that prints the addition value from the add function back to the function that calls it (in this case main). It won’t work, because add function only alters its copy of the value. In the calling function, when we try to print, we’ll get the original value, not the addition one!

There is a way to allow a function to alter the original value of variable holds, rather than a copy. We do this using pointers which also called as “pass-by-reference”.

Multiple Return Value⌗

One of Go’s unusual features is that functions and methods can return multiple values. This feature is quite useful in various situations where you need to return more than one piece of information from a function. Multiple return values allow you to efficiently handle errors, return status code, or return additional context information along with the primary result.

Below is Division program which return multiple values like quotient, remainder :

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func divideAndRemainder(dividend, divisor int) (int, int) {

quotient := dividend / divisor

remainder := dividend % divisor

return quotient, remainder

}

func main() {

quotient, remainder := divideAndRemainder(10, 3)

fmt.Printf("Quotient: %d, Remainder: %d\n", quotient, remainder)

}

In the above example, the divideAndRemainder function takes two integer parameters, dividend and divisor. It calculates the quotient and remainder of the division operation and returns both values as tuple (or pair) of integers. In Go, you specify the return types in parentheses immediately after the function signature. In below declaration (int, int) is returning pair of integers in function return value.

func divideAndRemainder(dividend, divisor int) (int, int) {}

When you call the divideAndRemainder function in the main function, you can capture both return values (quotient and remainder) and use them as needed.

Named Result Parameters⌗

Named Result Parameters allow us to declare names from the return values of a function in it’s signature. Named result parameters are particularly useful for improving the readability and documentation of a code. They make it clear what each return value represents and can be especially helpful in functions with multiple return values.

package main

import "fmt"

func divideAndRemainder(dividend, divisor int) (quotient int, remainder int) {

quotient = dividend / divisor

remainder = dividend % divisor

return

}

func main() {

q, r := divideAndRemainder(10, 3)

fmt.Printf("Quotient: %d, Remainder: %d\n", q, r)

}

In this example, the divideAndRemainder function has named result parameters quotient and remainder ((quotient int, remainder int)). Inside the function body, you assign values to these variables, and you don’t need to use the return statement explicitly. Go will automatically return the values of quotient and remainder when the function exits.

Benefits of using named result parameters:

**_Documentation and clarity_**: It provide self-documentation for the function, making it clear what each return value represents. This can improve code readability and maintainability.**_Simplify return statement_**: You don’t need to explicitly list thereturnvalues in the return statement. This simplifies the code and reduces redundancy.**_Avoid variable shadowing_**: When you use named result parameters, you can avoid variable shadowing issues that may occur if you redeclare the same variable names in a nested block.**_Facilitate readability in complex function _**: In functions with many return values or complex logic, using named result parameters can make it easier to understand the meaning of each return value.

Note:- Named result parameters are implicitly declared as local variables within the function. You can assign values to them directly, and they will be returned when the function exits. However,you cannot use the:=short declaration operator to declare and assign values to named result parameters withing the same line; you should use the=assignment operator.

Defer⌗

In Go, the defer statement is used to schedule a function call to be executed just before the surrounding function returns. It allows you to ensure that certain cleanup or finalization tasks are performed regardless of how the function exits, whether it’s due to normal execution or an error.

How defer statement works in Go:

**_Deferred functions are executed in reverse order_**: When you usedeferto schedule a function call, Go adds it to a stack. The deferred functions are executed in reverse order, meaning the last scheduled function will be executed first, and so on. This behavior is useful when you need to reverse some action or cleanup resources.**_Deferred functions capture their arguments at the time of the defer statement_**: If you pass arguments to a deferred function, those arguments are evaluated immediately, and their values are captured at the time of thedeferstatement, not at the time the function is executed. This can lead to some interesting behavior in cases where the values of variables change before the function executes.

A simple example to illustrate how defer works:

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("This will be executed last")

defer fmt.Println("This will be executed second")

fmt.Println("This will be executed first")

}

In this example, when the main function is executed, it first prints “This will be executed first,” then schedules the two fmt.Println functions using defer. These deferred functions will be executed in reverse order when the main function is about to return.

In practice, you often use defer for resource cleanup, like closing files, releasing locks, or other cleanup tasks, to ensure that these tasks are performed even if there’s an early return or an error condition.

Bullet Points⌗

- When a function returns multiple values, the last value usually has a type of

error. Error values have anError()method that returns a string describing the error. - By convention, functions return an error value of nil to indicate there are no errors.

- You can access the value a pointer holds by putting a * right before it: *myPointer.

- If a function receives a pointer as a parameter, and it updates the value at that pointer, then the updated value will still be visible outside the function.

Methods⌗

A function is a standalone piece of code that can be called by other parts of your program.

A method is a function that is associated with a specific type or struct.

The term method came up with object-oriented programming. In an OOP language (like C++ for example) you can define a class which encapsulates data and functions which belongs together. Those functions inside a class are called methods and you need an instance of that class to call such a method.

In Go, the terminology it is basically the same, although Go isn’t an OOP language in the classical meaning. A function which takes a receiver is usually called a method (probably just because people are still used to the terminology of OOP).

So, For example:

func MyFunction(a, b int) int {

return a + b

}

// Usage:

// MyFunction(1, 2)

but

type MyInteger int

func (a MyInteger) MyMethod(b int) int {

return a + b

}

// Usage:

// var x MyInteger = 1

// x.MyMethod(2)

Formatting Verbs⌗

| General | |

|---|---|

| %v | the value in a default format |

| %+v | when printing structs, adds field names |

| %#v | a Go-syntax representation of the value |

| %T | a Go-syntax representation of the type of the value |

| %% | a literal percent sign; consumes no values |

| Boolean | |

|---|---|

| %t | the word true or false |

| Integer | |

|---|---|

| %b | base 2 (binary) |

| %c | the character represented by the corresponding Unicode code point |

| %d | base 10 (decimal) |

| %o | base 8 (octal- uses number between 0 - 7) |

| %O | base 8 with 0o prefix |

| %q | a single-quoted character literal safely escaped with Go syntax |

| %x | base 16 (hexadecimal), with lowercase letters for a-f |

| %X | base 16 (hexadecimal), with uppercase letters for A-F |

| %U | Unicode format: U+1234; same as “U+%04X” |

| Floting-point and complex constituents | |

|---|---|

| %b | decimalless scientific notation with exponent a power of two |

| %e | scientific notation, e.g. -1.234456e+78 |

| %E | scientific notation, e.g. -1.234456E+78 |

| %f | decimal point but exponent, e.g. 123.456 |

| %F | synonym for %f |

| %9f | width 9, default precision |

| %.2f | default width, precision 2 |

| %9.2f | width 9, precision 2 |

| %9.f | width 9, precision 0 |

| %g | %e for large exponents, %f otherwise |

| %G | %E for large exponents, %F otherwise |

| %x | hexadecimal notation (with decimal power of two exponent), e.g. -0x1.23abcp+20 |

| %X | upper-case hexadecimal notation, e.g. -0X1.23ABCP+20 |

| String and slice of bytes | |

|---|---|

| %s | the uninterpreted bytes of the string or slice |

| %q | a double-quoted string safely escaped with Go syntax |

| %x | base 16, lower-case, two characters per byte |

| %X | base 16, upper-case, two characters per byte |

| Slice | |

|---|---|

| %p | address of 0th element in base 16 notation, with leading 0x |

| Pointer | |

|---|---|

| %p | base 16 notation, with leading 0x |

| The default format for %v is | |

|---|---|

| bool | %t |

| int, int8 etc. | %d |

| uint, uint8 etc. | %d, %#x if printed with %#v |

| float32, complex64, etc | %g |

| string | %s |

| chan | %p |

| pointer | %p |

| flags | |

|---|---|

| + | always print a sign for numeric values; guarantee ASCII-only output for %q (%+q) |

| - | pad with spaces on the right rather than the left (left-justify the field) |

| # | alternate format: add leading 0b for binary (%#b), 0 for octal (%#o) |

| ’ ’ (space) | leave a space for elided sign in numbers (% d); put spaces between bytes printing strings or slices in hex (% x, % X) |

| 0 | pad with leading zeros rather than spaces |

Data Structures⌗

Array⌗

An array is a collection of values that all share the same type. Think of it like one of those pill boxes with compartments – you can store and retrieve pills from each compartment separately, but it’s also easy to transport the container as a whole.

The values an array holds are called its elements. You can have an array of string, booleans, or an array of any other Go type (even an array of array). You can store an entire array in a single variable, and then access any element within the array that you need.

An array holds a specific number of elements, and it cannot grow or shrink. To declare a variable that holds an array you need to follow below syntax:

var myArray [4]string

var: Keyword to declare variable.myArray: Variable name which holds array.[4]string:[]: In this brackets you specify how much data array should hold. Like in above example[4]it will hold 4 elements.datatype: Which type of data it will store is mentioned here. for examplestringorint.

Elements in an array are numbered, starting with 0. An element’s number is called its index.

If you wanted to make an array with the names of people. for example, the first name would be assigned to index 0, the second name would be at 1, and so forth. The index is specified in square brackets.

var names [5]string // Create an array of five strings.

names[0] = "Goku" // Assign a value to the first element.

names[1] = "Vegeta" // Assign a value to the second element.

names[2] = "Gohan" // Assign a value to the third element.

fmt.Println(names[0]) // Print the first element.

fmt.Println(names[1]) // Print the second element.

// Output:

Goku

Vegeta

If you doesn’t assign a value to names[0] and try to print. It will show empty string lets see why.

Default values in arrays⌗

As with variables, when an array is created, all the values it contains are initialized to the zero value for the type that array holds. So an array of int values is filled with zeros by default and same will be for string but instead of zeros it will be empty string.

Zero/default values can make it safe to manipulate an array element even if you haven’t explicitly assigned a value to it. For example, here we have an array of integer counters. We can increment any of them without explicitly assigning a value first, because we know they will all start from 0.

var counters [3]int

counters[0]++ // Increment the first element from 0 to 1.

counters[0]++ // Increment the first element from 1 to 2.

counters[1]++ // Increment the third element from 0 to 1.

fmt.Println(counters[0], counters[1], counters[2])

2 0 1

/ | \

/ | Has been incremented once

/ Still at its zero value

Has been incremented twice

Note:- When an array is created, all the values it contains are initialized to the zero value for the type the array holds.

Okay, but how can assign default values like we do in python and other languages?

Array literals⌗

If you know in advance what values an array should hold, you can initialize the array with those values using an array literal. An array literal starts just like an array type, with the number of elements it will hold in square brackets, followed by the type of its elements. This is followed by a list in curly braces of the initial values each element should have. The element values should be separated by commas ,.

[3]int{7, 21, 5}

[3]: Number of elements array will hold.int: Type of elements array will hold.{data, comma, separated}: Comma-separated list of array values.

Let’s our previous example using array literals, instead of assigning values to the array elements one by one:

var names [4]string = [4]string{"Goku", "Vegeta", "Gohan"}

Using an array literal also allows you to do short variable declaration with :=.

names = [4]string{"Goku", "Vegeta", "Gohan"}

If you have array string with sentences as value:

text := [3]string{"This is a series of long strings", "which would be awkward to place", "together on a single line"}

As you see above it will be hard to read if item grow it will be in single line to make it more readable we can break this in multiline as shown below:

text := [3]string{

"This is a series of long strings",

"which would be awkward to place",

"together on a single line",

}

But here is catch which you will have to keep in mind when you break it in multiline it should end with , else you will get error/run it problems.

Slices⌗

It is a Go data structure that we can add more values to–it’s called slice. A slice is also a list of elements of a particular type, but unlike arrays, tools are available to add or remove elements. Slice don’t hold any data themselves. A slice is merely a view into the elements of an underlying array.

To declare the type for a variable that holds a slice, you use an empty pair of square brackets, followed by the type of elements the slice will hold.

var mySlice []string

This is just like the syntax for declaring an array variable, except that you don’t specify the size.

Unlike with array variables, declaring a slice variable doesn’t automatically create a slice. For that, we can call the built-in make function. We pass make the type of the slice we want to create which should be the same as the type of the variable we’re going to assign it to, and the length of slice it should create.

// Declare a slice variable

var notes []string

// Create a slice with seven strings

notes = make([]string, 7)

Once the slice is created, you assign and retrieve its elements using the same syntax you would for an array.

notes[0] = "go" // Assign a value to the first element

notes[1] = "ts" // ... to the second element

fmt.Println(notes[0]) // prints the first element

fmt.Println(notes[1]) // prints the second element

---Output---

go

ts

Here, we can prefer a short variable declaration with make. A short variable declaration will infer the variable’s type for you.

// Create a slice with five integers, and set up a variable to hold it.

numbers := make([]int, 5)

numbers[0] = 2

numbers[1] = 3

fmt.Println(numbers[0])

---Output---

2

The built-in len function works the same way with slices as it does with arrays. Just pass len a slice, and its length will be returned as an integer. Both for and for…range loops work just the same with slices as they do with arrays, too.

letters := []string{"a","b","c"}

// Regular for loop

for i := 0; i < len(letters); i++ {

fmt.Println(letters[i])

}

// For loop using range

for _, letter := range letters {

fmt.Println(letter)

}

Slice literals⌗

Create slices with initial values directly using slice literals:

- Syntax:

[]type{values}(e.g.,[]int{1,2,3}) - No need for

makefunction. - Resembles array literals, but without length in square brackets.

// Assign values using a slice literal.

notes := []string{"go","bot", "cool", "car", "ninja", "turtle"}

fmt.Println(notes[2], notes[4], notes[5])

// output

cool ninja turtle

The Slice Operator⌗

Every slice is built on top of an underlying array. It’s the underlying array that actually holds the slice’s data; the slice is merely a view into some (or all) of the array’s elements.

When we use the make function or a slice literal to create slice, the underlying array is created for us automatically. We can’t access it, expect through the slice. But we can also create a slice from array with the slice operator.

underlyingArray := [6]string{"go","bot", "cool", "car", "ninja", "turtle"}

slice1 := underlyingArray[0:3]

fmt.Println(slice1)

// Output

[go bot cool]

In tha above program underlyingArray[0:3] is creating slice using slice operator where it 0 is index of array where the slice should start, and the 3 index of the array that the slice should stop before. In above output we can see that the second index is the index the slice will stop before. That is, the slice should include the elements up to, but not including, the second index. If you use underlyingArray[i:j] as a slice operator, the resulting slice will actually contain the elements underlyingArray[i] through underlyingArray[j-1].

If you want a slice to include the last element of an underlying array, you actually specify a second index that’s one beyond the end of the array in your slice operator.

underlyingArray := [6]string{"go","bot", "cool", "car", "ninja", "turtle"}

slice1 := underlyingArray[3:6]

fmt.Println(slice1)

// Output

[car ninja turtle]

Make sure you don’t go any further than that, though, or you’ll get an error:

underlyingArray := [6]string{"go","bot", "cool", "car", "ninja", "turtle"}

slice1 := underlyingArray[3:7]

fmt.Println(slice1)

// Output

invalid argument: index 7 out of bounds [0:7]

Underlying arrays⌗

Constants⌗

Constants are just Constants in Go.

- Constants are created at compile time.

- It can be Character, String, Boolean, or Numeric values.

- Because of compile-time restriction, the expression define them must be constant expression, evaluated by a compiler.

For instance, 1«3 is a constant expression, while math.Sin(math.Pi/4) is not because the function call to math.Sin needs to happen at run time. -from go.dev/docs/effective_go

- Constants cannot be defined using short declarations (:=).

In Go, enumerated constants are created using the iota enumerator.

Embedding⌗

Not Embedding, just the declaration of two struct types working together:

type car struct {

name string

model string

}

type magazine struct {

company car // NOT Embedding

level string

}

This is embedding:

type car struct {

name string

model string

}

type magazine struct {

car // Value Semantic Embedding

level string

}

Embed a type using pointer semantics

type car struct {

name string

model string

}

type magazine struct {

*car // Pointer Semantic Embedding

level string

}

In this case, a pointer of the type is embedded. In either case, accessing the embedded value is done through the use of the type’s name.

The best way to think about embedding is to view the car type as an inner type and magazine as an outer type. It’s this inner/outer type relationship that is magical because with embedding, related to the inner type (both fields and methods) can be promoted up to the outer type.

package main

import "fmt"

type car struct {

name string

model string

}

type magazine struct {

*car // Pointer Semantic Embedding

level string

}

func (c *car) order(quantity int) {

fmt.Printf("Ordering %d copies of magazine \"%s\" (%s).\n", quantity, c.name, c.model)

}

func main() {

mz := magazine{

car: &car{name: "Honda Accord", model: "2024"},

level: "Gold",

}

mz.car.order(2)

mz.order(3) // Outer type promotion

}

// Output:

// Ordering 2 copies of magazine "Honda Accord" (2024).

// Ordering 3 copies of magazine "Honda Accord" (2024).

Once I add a method named order for car type and then a small main function, I can see the output is the same whether I call the order method through the inner pointer value directly or through the outer type value. The order method declared for the user type is accessible directly by the magazine type value.

Composition⌗

The best way to take advantage of embedding is through the compositional design pattern. The idea is to compose larger types from smaller types and focus on the composition of behavior.

type Cloud struct {

Host string

Timeout time.Duration

}

func (*Cloud) Pull(d *Data) error {

switch rand.Intn(10) {

case 1, 9:

return io.EOF

case 5:

return errors.New("Error reading data from Cloud")

default:

d.Line = "Data"

fmt.Println("In:", d.Line)

return nil

}

}

The Cloud type represents a system that I need to pull data from. The implementation is not important. The method Pull can succeed, fail, or not have any data to pull.

type DB struct {

Host string

Timeout time.Duration

}

func (*DB) Store(d *Data) error {

fmt.Println("Out:", d.Line)

return nil

}

The DB type also represents a system that I need to store data into. The method Store can succeed or fail.

Note:- Above both methods implementation is not important here. Ignore the implementation.

These two types represent a primitive layer of code that provides the base behavior required to solve the business problem of pulling data out of Cloud and storing that data into DB.

func Pull(c *Cloud, data []Data) (int, error) {

for i := range data {

if err := c.Pull(&data[i]); err != nil {

return i, err

}

}

return len(data), nil

}

func Store(d *DB, data []Data) (int, error) {

for i := range data {

if err := d.Store(&data[i]); err != nil {

return i, err

}

}

return len(data), nil

}

These two functions, Pull and Store are build on the primitive layer of code by accepting a collection of data values to pull or store in the respective systems. These functions focus on the concrete types of Cloud and DB since those are the systems the program needs to work with at this time.

func Copy(sys *System, batch int) error {

data := make([]Data, batch)

for {

i, err := Pull(&sys.Cloud, data)

if i > 0 {

if _, err := Store(&sys.DB, data[:i]); err != nil {

return err

}

}

if err != nil {

return err

}

}

}

The Copy function builds on top of the Pull and Store functions to move all the data that is pending for each run. If I notice the first parameter to Copy, it’s a type called System.

type System struct {

Cloud

DB

}

The System type is to compose a system that knows how to Pull and Store. In this case, composing the ability to Pull and Store from Cloud and DB.

func main() {

sys := System{

Cloud: Cloud{

Host: "localhost:8000",

Timeout: time.Second,

},

DB: DB{

Host: "localhost:9000",

Timeout: time.Second,

},

}

if err := Copy(&sys, 3); err != io.EOF {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}

The main function can be written to construct a Cloud and DB within th composition of a System. Then the System can be passed to the Copy function and data can begin to flow between the two systems.

Now I have our first draft of a concrete solution to a concrete problem.

Decoupling With Interfaces⌗

Methods⌗

A function is called a method when that function has a receiver declared. The receiver is the parameter that is declared between the keyword func and the function name. There are two types of receivers, value receivers for implementing value semantics and pointer receivers for implementing pointer semantics.

type user struct {

name string

email string

}

func (u user) notify() {

fmt.Printf("Sending User Email To %s<%s>\n", u.name, u.email)

}

func (u *user) changeEmail(email string) {

u.email = email

fmt.Printf("Changed user email to %s\n", email)

}

The notify function is implemented with a value receiver. This means the method operates under value semantics and will operate on its own copy of the value used to make the call. (It will get the copy of value so if we update it will not affect outside method.)

the changeEmail function is implemented with a pointer receiver. This means the method operates under pointer semantics and will operate on shared access to the value used to make the call. (It will update the value in struct.)

Interfaces⌗

Interfaces give programs structure and encourage design by composition. They enable and enforce clean division between components. The standardization of interfaces can set clear and consistent expectation.

Decoupling means reducing the dependencies between components and the types they use. This leads to correctness, quality and maintainability.

Interface allow me to groupe concrete data together by what the data can do. It’s about focusing on what data can do and not what the data is. Interface also help my code decouple itself from change by asking concrete data based on what it can do. It’s not limited to one type of data.

Interfaces should describe behavior and not state. They should be verbs and not nouns.

Use an interface when:

- Users of the API need to provide an implementation detail.

- API’s have multiple implementations they need to maintain internally.

- Parts of the API that can change have been identified and require decoupling.

Don’t use an interface:

- For the sake of using an interface.

- To generalize an algorithm.

- When users can declare their own interfaces.

- If it’s not clear how the interface makes the code better.